The practice of art is an organised anomaly. It is disciplined in language.

Other than this there is only chit-chat about “creativity”. The work of Paolo

Monti has constantly revolved around this evidence and this awareness, through

the filter (and code) of an instrumentation that ranges from the most prosaic

manuability to the most sophisticated scientific-technological apparatus.

Perhaps it is because of this that he appears as the catalysing fulcrum (or

disperser?) of a series of references, fundamental problems and questions that

are divided into two distinct, but tightly interconnected, conceptual and

operative routes.

On one hand his work with money, and consequently the fetichism of Value: desire

not of the object, but of desire itself. A vertigo of the most complete

abstraction, of the most discarnate virtuality whilst at the same time

representing the utmost factual operativity possible, with the

theoretic-conceptual route traceable from Marx to Simmel. Monti therefore takes

money, both conceptually and materially, as the object of his work; figure of

itself and of the Other: vertigo of Value, mythology of the Myth. But which are

the elements put into play?

“The exchange value of goods, in as much as a particular entity parallel to the

goods” wrote Karl Marx in the Grundrisse, “is money; it is the form in which all

goods are equivalent, are confronted, are measured; it is that in which all

goods are dissolved, that which is dissolved in all goods”. The work of Paolo

Monti seems to be both the paraphrase and the literal reversal of Marx’s thesis.

Money is not in fact assumed as a form or a means and, therefore, as a general

equivalent, but as material subjected to a specific process of perishability: it

dissolves not into goods but into itself. The abstract sign regresses into

concrete, physical fact in present (temporaneous) consistency. Money is not by

nature a commodity endowed with intrinsic value, its quality consists

exclusively in its quantity. Monti materialises abstract value, the phantom; he

reverses the process that leads to the exclusion of the goods assumed as money

and therefore the general equivalent, bringing money back to its initial

condition of material-object with its extreme residual value of use. In a given

time, the banknote attacked by acids will dissolve, until there is no trace

left. It is said that “time is money”. Here it is money that is time. Until

total entropy is reached, until the final consummation. Until nothingness.

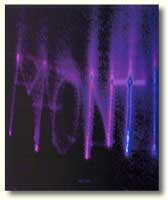

On the other hand, his work that most explicitly adheres to

scientific-epistemological procedures, concentrating on a hyper-technological

dimension and fundamentally radicated in the principles of sensitive perception

-and in the interrogatives raised by this- regarding the relationship between

subject and object; identity and alterity (Otherness).

That the “object” is in reality a world, a horizon of sensibility that

nevertheless brings to life an aesthetic experience, is another question. The

fact remains that it is the Other that constitutes us; without forgetting

obviously that we ourselves are others to the others. Any kind of proximity

cannot originate without this distance.

All these things are well known. Here they are recalled in very synthetic terms

only because they have something to do with (maybe more than that which might

appear at first glance), the more sophisticated technological work of Paolo

Monti. The themes are exactly those of the relationship between identity and

alterity, between subject and object: with their reciprocal exchange and

deviations within the cognitive labyrinths which bind them to one another. An

interactive practice, whereby it is the spectator that renders the manifestation

of the opera as such possible.

Paolo Monti’s work certainly reveals the “marvellous”, the (hyper) technological

thaumazein: at various levels of power and seduction, but it is undoubtedly

revealed. In fact, technological processes (based on physics or chemistry) are

simply shown without any particularly intrusive elaboration on the part of the

artist. Monti is not in search of the “imaginative”, “aesthetic” side of

Technique; nor does he possess the pathetic ideological pretension of

humanistically redeeming Technique through “poetry” or “creativity”. Here,

technology is utilised in a way in which it autonomously and spontaneously

produces the true thaumazein. But for this to occur, it must -with Duchampian

memory- be “put it into place”. And this, only an artist can do.

Massimo Carboni,

Professor of Aesthetics at the Faculty of Arts and Culture of the University of Tuscia in Viterbo and the Accademia di Belle Arti

Firenze / Academy of Fine Arts of Florence, Italy

Massimo Carboni,

Professor of Aesthetics at the Faculty of Arts and Culture of the University of Tuscia in Viterbo and the Accademia di Belle Arti

Firenze / Academy of Fine Arts of Florence, Italy

...

excerpt form: “Until Nothingness” by

Massimo Carboni in

«Paolo Monti» (Musis, 1998) ISBN

88-87054-01-0 and presented in the collection of selected

texts produced for the personal exhibition of Paolo Monti,

Vierdimensional², Konstanz (Germany), 2001.