|

Money, its depiction and the fourth

dimension. . .

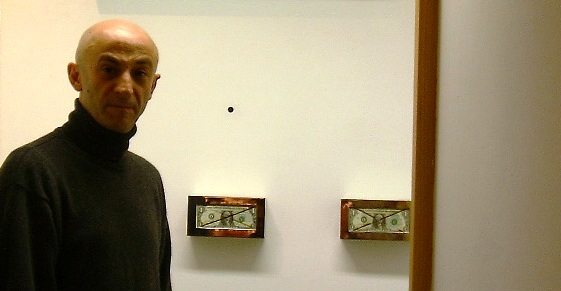

The works of Paolo Monti

Fiedermann Malsch,

Director of the Liechtenstein Art Museum

When I met Paolo Monti in the early nineties, he showed me several works with a

single subject: the banknote. Piled up, cut up or processed in various other

ways, all those banknotes rotated around a single abstract concept, the system

used to determine the value of the banknote. At first sight, Monti seemed to be

following in the footsteps of Joseph Beuys and Marcel Broodthaers, both, in

different ways (one “engagé” the other ironical) disciples of the prophet Marcel

Duchamp and his insistence on the contextuality of art. Particularly in his

“ready-made” Duchamp drew his audience’s attention to the fact that art

inevitably exists inside the broader social and temporal context of its day and

insisted that it should not cut itself off from that context.

In following the Duchamp line, Joseph Beuys was more analytically motivated and

applied his approach to the socio-political commitments of various avant garde

groups up to and including the surrealists. He developed his own system of

economic values, the essentials of which were summed up in the statement that

emerged from the “Bitburger Talks” of early 1978: «But what is CAPITAL… since it

can only be the product of man’s capacity to make things that output at its most

bounteous is art and at its most concrete is CAPITAL. ART = CAPITAL ».

Any phenomenological analysis of the flow of economic values in the production

process will identify economic value 1 as output capacity (creativity), economic

value 2. as the spiritual or physical goods produced by combining work capacity

with the raw materials supplied by nature. This makes the tools involved

resources at a higher level of development. In this process there is no economic

value that can be identified, as we do today, as the property of MONEY. Though

Beuys’s economic values are equally intangible, what distinguishes them from

money is their bond with natural capacities of man who is the hub of all

economic activities. MONEY HAS BEEN EMANCIPATED to become the legally recognised

regulator of all economic processes. In the DEMOCRATIC CENTRAL BANKING SYSTEM

money has been created out of nothing. [1]

The less ideologically committed Andy Warhol or Robert Watts settled for mere

irony in presenting the banknote as an “art product”. In his seventies paintings

copied dollar bills in arbitrarily selected numbers and arrangements. For his

part, Watts spotlighted the absurdity of our collectors’ greed for banknotes in

works like his “Dollar bill in wood chest” (c. 1976) which places three piles of

fake dollars inside a carefully handcrafted, made-to-measure wooden casket. By

contrast, Marcel Broodthaers’ works repeatedly focused on the relationship

between art appreciation and the art market in order to undermine it with irony.

Even so, his approach has more in common with the detachment of a Marcel

Duchamp. In his 1991 work, “Die Bank”, Thomas Huber makes a much more forceful

attack in the money maker, picking up the core ideas of Joseph Beuys but

treating comparability in a more poetic fashion.

Paolo Monti’s approach is quite different and distinctively his own. He is less

interested in the overall social contest of money than in the formal

characteristics of the banknote and the paradoxical logic that governs its

operations. Many of his works directly counterpose the physical presence of the

banknote and the tendentially absurd, abstract concept of monetary value. In

these works, money, which Beuys himself had already proclaimed “autonomised”

seems to be trapped inside its own frame of reference. What the artist does is “liberate” money by treating his banknotes with chemicals that, over time, leach

out the material base from the abstract value. What that means is that once

released from its “earthly” shackles of paper and shape, the abstract value is

free to return to the space-time continuum, to the fourth dimension. banknote and the tendentially absurd, abstract concept of monetary value. In

these works, money, which Beuys himself had already proclaimed “autonomised”

seems to be trapped inside its own frame of reference. What the artist does is “liberate” money by treating his banknotes with chemicals that, over time, leach

out the material base from the abstract value. What that means is that once

released from its “earthly” shackles of paper and shape, the abstract value is

free to return to the space-time continuum, to the fourth dimension.

Monti takes his own line at one other level as well. His works of recent years,

in particular, have taken a surprising turn towards the general theme of ways to

represent non-visible phenomena. This leads to unusual associations between

cultural and monetary phenomena, two aspects that had always been treated as

antithetical in the past. The key concept in these later works is equivalence,

which can be applied both to the monetary system and to the fundamental

aesthetic aspects of the figurative arts. For example, in the composition of a

painting or a sculpture, the relative weight of the works’ various elements

plays a decisive role. When it comes to the point of intersection between money

and art, the question of equivalence is posed as follows: «Is there an

equivalence between art and money in terms of each system’s concepts of

equilibrium and equivalence?».

While we can speak of equilibrium in discussing total monetary flows inside a

given economic policy, the question of equivalence primarily takes the following

form: what is the value of this or that sum of money? The answer would appear to

be a simple one that covers all the almost infinite number of different goods we

can buy with money at any given time, but what is the value of a work of art?

Clearly we would not expect that to be indicated primarily by its market price,

though a sum of money is obviously one of the many possible equivalents of an

art work. Picasso, indeed, may have hit the nail on the head when he told the

lady who asked what a painting of his represented: «Madame, this picture

represents twenty million francs».[2]

However, if we bear Beuys’s concepts in mind, it is clear what Paolo Monti’s

intentions are. Equivalence in the sense of “correspondence” creates a link

between the abstract values the artist has “liberated” and the properties of the

human. But then, what are these properties? And can they too be effectively

represented, ie abstracted? This takes us back to an age-old problem of the

figurative arts, one that goes back as far as Plato: what does an image

represent? The question is posed with the utmost clarity in Monti’s latest works

which involve photographic images of the different temperature zones in the

human body. The photographic technique employed visualises certain chemical and

physical processes in the human body, but also the outline of the human figure

photographed. In a very real sense, therefore, these photographs are portraits. Schiebler has something to say about this too: «Since equivalent does not mean

equal, it cannot be a question of substitution (but rather transposition,

transformation, metabolisation). A portrait is not a substitute for its sitter,

but a reality on its own account, which in some respect has less and in others

more value than the person portrayed. Moreover, the sitter cannot be the

equivalent of his portrait or why would portrait of the same sitter by different

artists have different values. The actual equivalent is the image created in the

artists’ mind. Fragile and subjective, that image however could only be brought

into being via a medium of the same nature in the observers mind. Only money and

art possess this dual ability to be both subjected to an extremely complex

regulatory system and, the same time, to possess a universal capacity to achieve

liberation. What they do with it depends, in both cases, on their users. [3]

Monti uses the portrait (mostly of himself) to carry the concept of equivalence

to its illogical conclusion. In doing so, he assigns a substantial role to the

logical and formal aspects of the matter. However, despite their attractive

colours and recognizable human figures, these pictures give the impression of an

existential vacuum. Here too, his printings operate inside their own frame of

reference that tends to be purely self-referential.

However, since, as already stated, Monti’s deliberations, despite their

circumlocutory logical convolutions, always converge upon an existential plane,

his portraits, like all his other works, are rationally constructed: like the

human figure they represent, Monti’s portraits are subject to the ravages of

time and decay into unrecognizability. Here too, what happens is the liberation

of abstract value (in this case the value of the man whose image is depicted) in

a space-time continuum that cannot be represented, in the fourth dimension. And

in that dimension every avenue for experimental exploration is again open. In

this way Monti wins back for alchemy its freedom of action in both the rational

(money) and non-rational (art) environments. Which gives one some hope for the

future.

Fiedermann Malsch

Vaduz, December 2000

[1] The Money Museum: The strange value of money in art, science and life.

[2] The fifth element: money or art

[3] ibid.

|