|

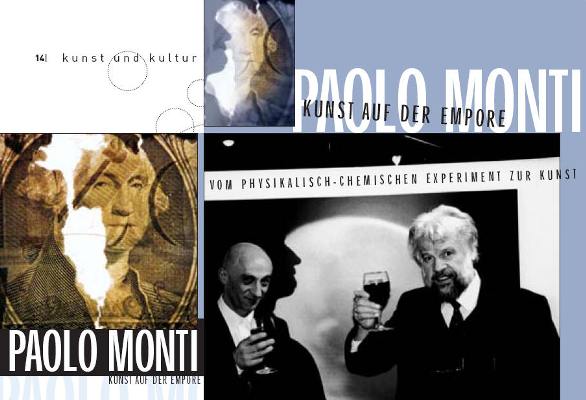

PAOLO MONTI:

from physical-chemical experiment to art

14 | a r t & c u l t u r

e

|

uni’kon | Alexia

Sailer II.2001

The shape seems to be

permeated by mysterious force fields.

Cloudlike configurations of yellow-orange shades fill the face and

bare arms of the figure. A shirt and cap can be deciphered, defined

by patches of lilac-blue.

The realisation dawns: here you see the image of a man taken with a

thermal camera. The principle of this procedure is the heat from the

instrument as it depicts temperature; the warmer the object the more

its pictorial representation glides into a deep orange. The colder,

the colour shifts to blue. What was displayed up there in the

gallery of the university is perhaps a scientific discovery created

through image? Yes, but not only.

"Four-Dimensional", was the title of the exhibition of Italian

artist Paolo Monti.

An exposition that combines science, or rather, art and

experimentation.

Thermal images are a part of Paolo Monti's work in the 90s. It is

with this technique that he creates portraits. However, no longer

portraits depicting the immutable appearance that tends to affix

characteristic features of a person in the image. Paolo Monti,

through scientific experimentation, utilizing mirrors of mercury,

creates portraits beyond the individual, no longer tied to a

personality.

The question arises: what is art in Monti? The answer is conceivably

to be found in a work in which the shadow of the profile of the

artist overlaps with the profile of the artist in a thermal image.

And this alludes to the anecdote of the beginnings of painting, when

a woman drew the silhouette of her beloved who went away to war.

Monti presented conceptual art "à la Duchamp," as explained by

Friedemann Malsch, director of the Kunstmuseum of Liechtenstein,

when introducing the show.

This aspect is also apparent in the second series of works - to

which Paolo Monti is committed - namely Money. Or rather, decay and

decomposition of money. Works such as the installation "Take a

sniff, it smells good!" create hilarity and respire profound

meaning.

To watch the dissolution of a dollar bill and see evidence of the

collapse of money, fixed on CIBA chrome, awakens curiosity and of

course brings with it many implications. Even so, was it not a bit

exaggerated to put Monti on the same level of multilayered

innovation and deeply reflective horizon of meaning as a Marcel

Duchamp?

Professor Nikolaus Läufer, economist at Constance, correlates the

work of Monti with a particular monetary theory. Läufer recalls the

so-called "Schwundgeld" (play money), invented by Silvio Gesell in

the 1930s. At the time, the concern was that saving money was

damaging the economy. To kick-start the financial system, money must

deteriorate so that the fortunate owners of capital would invest

their wealth immediately, before the collapse.

The implications were clear: Paolo Monti also produces a form of

hypothetical currency: on one hand the money destroys itself through

chemical decomposition; in the case of "Take a sniff, it smells

good! " the observer, by pressing a button, becomes actively

destructive. Of course the artist himself had his hands in the game,

creating a texture, by slicing off the top edges of Italian 50,000

lira banknotes and encapsulating them between two sheets of

plexiglass.

Monti, subsequent to all this work, from the "magical dissolution"

of money, arrives at the multiplication of money; as Friedemann

Malsch explained chuckling during the Vernissage: Paolo Monti went

to the bank with "circumcised bills" and exchanged them

unceremoniously for new ones.

Alexia Sailer

|